Exploiting Virtual Economies: A Historical Analysis

Habitat (1985), Ultima Online (1997), EverQuest (1999) and EVE Online (2003)

Introduction

Virtual economies are the beating heart of many online games, shaping player interactions, progression, and even real-world value exchanges. While these systems are designed to enhance engagement and provide depth, they are also susceptible to exploitation-sometimes on a scale that rivals real-world financial scandals. From the earliest graphical multiplayer games to blockchain-powered metaverses, players have repeatedly uncovered and leveraged vulnerabilities, often forcing developers to intervene with drastic measures. This paper examines five landmark case studies-Habitat (1985), Ultima Online (1997), EverQuest (1999), and EVE Online (2003)-to analyze how players have exploited in-game currencies, the economic principles these disruptions reveal, and the lessons for future virtual economy design.

Habitat (1985): The Birth of Virtual Arbitrage

Game Mechanics and Economic Framework

Developed by Lucasfilm, Habitat was a pioneering graphical MMORPG where players interacted in a shared 2D world using Commodore 64 computers. The economy revolved around Tokens, earned through activities like mining and spent at automated vendors ("Vendroids") or pawn shops. Key features included:

Static Pricing: Vendroids sold items at fixed rates (e.g., dolls for 75 Tokens).

Player Trading: Pawn shops allowed players to sell items back at predetermined prices.

The Arbitrage Exploit

Players discovered a critical pricing mismatch:

Doll Arbitrage: Vendroids sold dolls for 75 Tokens, while pawn shops bought them for 100 Tokens.

Crystal Ball Exploit: Crystal balls cost 18,000 Tokens to purchase but could be sold for 30,000 Tokens.

By shuttling between locations, players generated infinite wealth. In one night, three users quintupled the game’s money supply, accumulating "hundreds of thousands of Tokens each". The resulting hyperinflation rendered standard earnings (≈100 Tokens/day) meaningless, destabilizing the economy.

Systemic Weaknesses

No Dynamic Pricing: Fixed rates ignored supply-demand dynamics.

Absence of Currency Sinks: Tokens entered circulation but never exited, leading to unchecked inflation.

Ultima Online (1997): Hyperinflation and the Great Gold Purge

Game Mechanics and Economic Framework

Ultima Online (UO), released in 1997, pioneered persistent virtual worlds with a player-driven economy centered on gold pieces. Key features included:

Gold Sources: Earned through defeating monsters, crafting, and selling items to NPC vendors.

Currency Sinks: Housing deeds (costing millions of gold) and vendor rent fees.

Storage Limits: Banks capped gold storage at 7.5 million per account, forcing players to use checks for larger sums.

Exploit Mechanics: The Check Duplication Crisis

In 2006, players exploited a loophole in the check system:

Oversized Checks: Intended to cap at 1 million gold, checks were manipulated to store trillions of gold.

Arbitrage and Hoarding: Players used these checks to bypass storage limits, amassing 15 trillion gold-equivalent to $15–60 million in real-world value based on eBay sales ($1–4 per million gold).

Impact and Developer Response

Economic Collapse: Hyperinflation rendered standard gold-earning activities (e.g., killing monsters for ~100 gold) meaningless. Housing markets became inaccessible to new players due to inflated prices.

EA’s Intervention: In July 2006, EA removed 15 trillion gold and banned 180+ accounts. Legitimate players with oversized checks faced complex recovery processes, including subdivided checks in "brown bags."

Systemic Weaknesses

Static Check Limits: Fixed caps ignored player wealth accumulation, forcing reliance on checks.

Third-Party Trading: Unregulated RMT (Real-Money Trading) platforms enabled gold laundering, with eBay sellers profiting from illicit gains.

Moderation Challenges: The 2007 "gold duplication bug" required repeated purges, eroding player trust.

EverQuest (1999): Mudflation and the Rise of Real-Money Trading

Game Design and Economic Model

EverQuest, a 3D fantasy MMORPG, featured a gold-based economy where players earned currency by defeating enemies. Key mechanics included:

Cohort Staging: New players entered an expanding world, increasing the money supply through grinding.

Asset Deflation: Veterans discarded low-tier gear, flooding markets and depressing prices.

Consequences

Economist Edward Castronova’s 2001 study revealed:

68% of players lived below the game’s mean income, exceeding real-world U.S. wealth disparity.

EverQuest’s per-capita GNP ($2,266) rivaled Bulgaria’s, with platinum pieces surpassing the Japanese yen’s value.

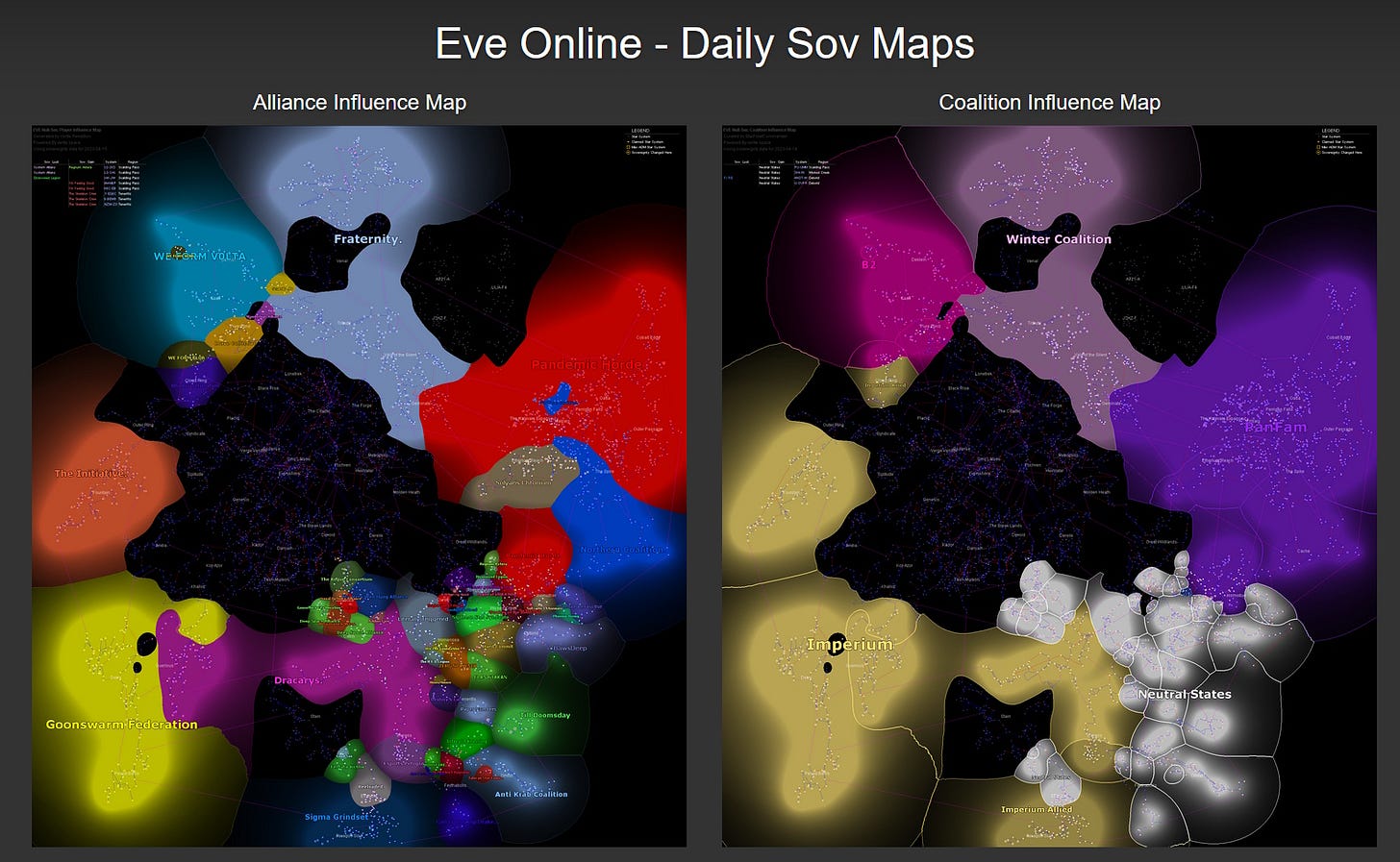

EVE Online (2003): Player-Driven Crises and the Cost of Freedom

Economic Structure

EVE Online’s player-driven economy relies on ISK (Interstellar Kredits), earned through resource mining, manufacturing, and PvP. Currency enters via mission rewards and exits via asset destruction.

Exploits and Market Manipulation

The Battle of B-R5RB (2014): A soviet bill payment error triggered a 21-hour conflict destroying 75 titans (≈$300K real-world value). While this removed ISK via ship losses, developer CCP Games later exacerbated inflation by reducing resource availability, causing stagflation.

EVE Intergalactic Bank Scam: A player-run Ponzi scheme collapsed, stealing 790 billion ISK (≈$29K real-world value) and highlighting the risks of unregulated markets.

Vulnerabilities

Centralized Scarcity: Developer interventions disrupted organic player strategies.

Speculative Hoarding: Players stockpiled resources during updates, distorting prices.

Cross-Game Vulnerabilities and Economic Principles

Arbitrage and Static Pricing

From Habitat’s doll arbitrage to Ultima Online’s check exploits, fixed pricing in automated systems invites exploitation. Dynamic algorithms adjusting rates based on transaction volume could mitigate this.

Currency Sinks and Inflation Control

EVE’s PvP destruction and Ultima Online’s housing deeds demonstrate the necessity of sinks. EverQuest’s lack thereof led to irreversible mudflation.

Real-Money Trading (RMT)

RMT destabilizes economies by introducing external incentives. Ultima Online’s eBay bans highlight the need for controlled, developer-sanctioned RMT platforms.

Conclusion: Lessons for Future Virtual Economies

Key Takeaways

Dynamic Pricing: Algorithmic adjustments to prevent arbitrage (Habitat, Ultima Online).

Transparent Governance: Clear rules for currency sinks and updates (EVE Online).

Future Directions

Regulated RMT Platforms: Developer-controlled markets to curb third-party exploitation (Ultima Online).

Player-Centric Design: Balancing economic freedom with safeguards against hoarding and fraud.

As virtual economies grow in complexity, historical lessons from Habitat to Eve Online remain vital. By addressing these vulnerabilities, designers can create resilient systems that captivate players without sacrificing stability-a challenge as old as virtual worlds themselves.

This synthesis provides a comprehensive view of how virtual economies have been shaped, challenged, and sometimes upended by the ingenuity of their participants and the responses of their creators.